Chapter Two

Mikovits shares that her desire to become a doctor was triggered by seeing her grandfather struggle with and eventually die from lung cancer when she was ten years old. In her last year in her undergraduate degree, she happened to see an article on interferon which is a natural substance (which can also be created in the laboratory) that helps the body fight viral infection. It is a signalling protein released from host cells infected with a virus that ‘warns’ other cells to heighten their response to viral attack.

Initially interferon was hailed as if it could be a new wonder drug. So called due to its ability to ‘interfere’ with viral spread. However, its popularity waned in the late twentieth century due to sometimes severe side effects such as depression. Alternatives have been developed which have a more targeted response to certain illnesses. In 1980, having graduated from the University of Virginia earlier that year with a BA in Chemistry, Mikovits found employment working for the National Cancer Institute (NCI) as a lab technician researching into interferon. Serendipity!

Six years later, Mikovits left the NCI as the Biological Response Modifier (BRM) programme she had been working on had been dissolved by the government. BRMs, one of which is interferon itself, can be used to fight foreign bodies including autoimmune diseases. Regarding cancer, for example, chemotherapy and radiation target the cancerous cells directly, whereas BRMs enhance the immune system’s ability to combat and destroy them.

Mikovits also briefly mentioned another event at the time at the NCI which could have also contributed to her decision to leave. Specifically, she observed a young Japanese scientist engaged in postdoctoral research being instructed to change data in an experiment by a senior researcher. Mokovits says he was clearly troubled by this instruction and committed suicide shortly afterwards. Mikovits reported the incident to her line manager who took no action. Mikovits then started working at a private company called Upjohn Pharmaceuticals in 1986 as a Lab Technician in the Quality Control Department. So, Mikovits transferred from a governmental organization to a private one. She debates which sector is better to work for. The former should be free of bias and politics whereas the second has more money to invest in programmes that could save many lives. In the end, she feels it all depends on the integrity of the management regardless of whether the organization is in the public or private sector.

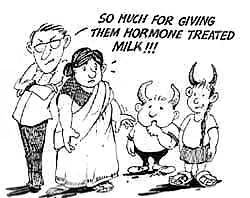

Working at Upjohn, Mikovits shares two particular aspects of her research work there in the capacity of a laboratory technician. One was positive for the profitability of the company while the other was decidedly negative and it was the latter that led her to her premature departure from Upjohn. To wit, Mikovits’ role focused on researching into the safety of the company’s bovine growth hormone which Upjohn was marketing to farmers to accelerate cow growth and milk production. It was her remit to ascertain whether or not this hormone had any negative side effects on humans.

However, Mikovits had to delay working on this as she was called away to work on ATGAM administered to those who have received transplants. The product was derived from human and horse blood and the company wanted to be certain that the blood they were using had not been contaminated with HIV. Anti-Thymocyte Globulin (Equine) (ATGAM) is a drug that targets and suppresses the immune system so that it is less likely to reject an organ transplant or tissue graft. Specifically, the activity of T Lymphocytes (white blood cells involved in immune responses) is suppressed and neutralized. It is often used with kidney transplants. Mikovits’ laboratory experiments confirmed that the manufacturing process involved in creating ATGAM was successful in destroying any HIV cells present.

Conversely, the outcome of her research regarding the company’s bovine growth hormone had opposite results. Mikovits soon noticed while carrying out her quality control work that the hormone was affecting the morphology (form) of some fat cells (adipocytes). Specifically, she noticed ‘blebbing’ or blistering of the cell membrane causing irregular bulges in the fat cell walls. Further research confirmed her fears that the product was indeed unsafe due to these abnormalities. This discovery coincided with a request from her mother to return home to support her step-father who was suffering from cancer. If she agreed, she would be within ten miles of Bethesda, Maryland and her old employers at the National Cancer Institute.

Mikovitz decided to go and again found work at the NCI helped by her long-standing relationship with mentor, Frank Ruscetti who still worked there and who additionally, at the same time, was instrumental in securing Mikovitz a place on a graduate degree course at George Washington University on her return to the NCI. Mikovits turned for advice to Ruscetti regarding her concerns about the Bovine Growth Hormone. Specifically, Mikovits wondered if latent retroviruses dormant in the human body could be activated by the presence of abnormal cells such as those she had identified in her current research. Such viruses are called endogenous retroviruses (ERVs). Ruscetti was indeed the right person to ask. Mikovits asked if a dormant bovine leukemia virus (BLV) could become active again due to the bovine growth hormone. Ruscetti had indeed published papers on BLV and was the first researcher to isolate the first disease-causing retrovirus, HTLV-1, a leukemia virus. Ruscetti believed that Mikovits’ doubts were justified. Furthermore in 2015, University of California scientists made public the findings of their similar research. Namely, they had identified BLV in the breast cancer of 239 women, adding more weight to the argument.